Chief People Officer Of The Future: Three Key Changes Ahead For The CHRO Role

New research shows that people management executives are moving toward a dual role as data scientists and guardians of change and culture. Chief People Officers are seeing a transformation of their role in three key areas: using data and technology while remaining attuned to fundamentally human concerns; addressing employees’ emotions and wellbeing at work; and attracting skilled employees from more diverse backgrounds.

This article originally appeared in The Adecco Group.

How can leaders support employees to do their best at work, while also creating a better world of work? Chief People Officers are seeing a transformation of their role in three key areas: using data and technology while remaining attuned to fundamentally human concerns; addressing employees’ emotions and wellbeing at work; and attracting skilled employees from more diverse backgrounds.

The Adecco Group partnered with the University of Zurich’s Center for Leadership in the Future of Work to explore how the evolving world of work is changing the role of the Chief People Officer, or CPO – a role also known by titles such as Chief Human Resources Officer or Head of Talent. We gathered the opinions of 122 executives for a newly published study, The Chief People Officer of the Future.

Conducted in summer 2021, our survey gathered the opinions of 122 executives in human resources from 10 countries across the globe: Australia, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, Mexico, Spain, Switzerland, UK and US. Together they are responsible for over 3 million employees in a range of sectors, from finance to retail to aerospace. Here are our three main findings.

1. CPOs are shifting from traditional managers to data scientists and guardians of culture

We asked the executives to reflect on how they spend their time now, and how they expect to spend their time in the future. The foresee spending less time in future on traditional management tasks, such as managing teams and core HR functions, and compliance and regulatory procedures.

They expect to spend more time on two areas: engaging with data; and driving organisational change and culture. To get a sense of timeframe, we randomly asked some respondents to look five years ahead, and others 20 years ahead. Those looking five years ahead anticipated data and people analytics demanding relatively more time, while those looking 20 years ahead put more weight on creativity and human skills.

These findings point to a possible source of tension for the future CPO. Companies may need to consider whether the CPO role would be better separated into two roles – one focused on data and technology, the other specialised in addressing the human concerns related to company culture. However, splitting the role could lead to missed opportunities to use data to shape people practices in a human-centered way.

If companies expect the executive role to continue to combine data science with culture guardianship, they may need to identify in which of these two areas their leaders feel that their skills need the most improvement. The more long-term the perspective an organisation takes, the more it may prioritise developing the role in a more human-centric direction than focusing on data and tech.

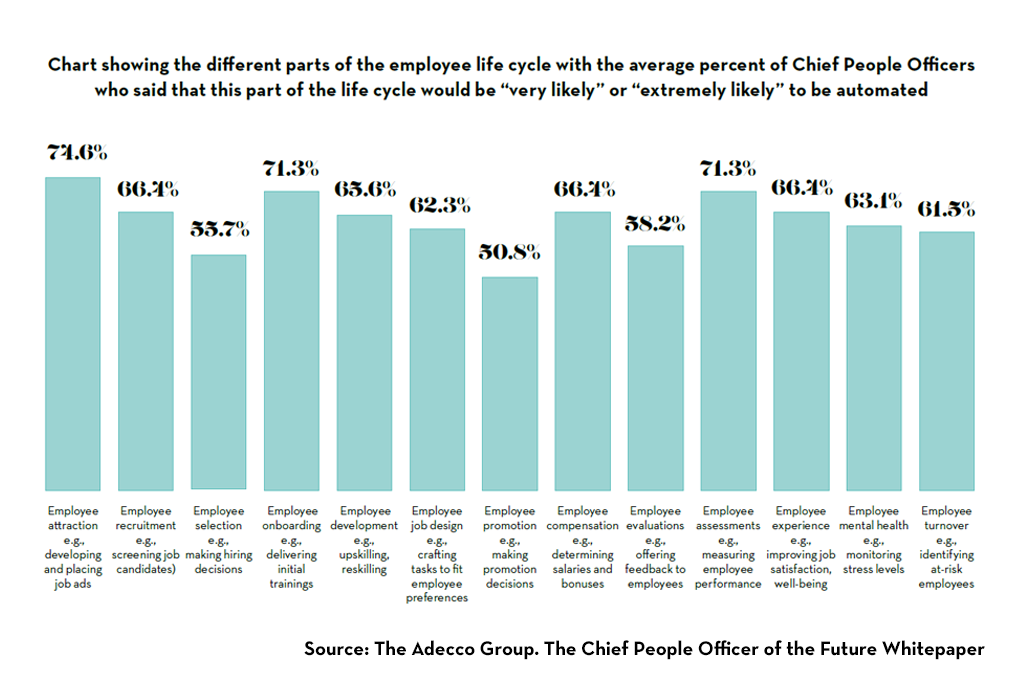

We also asked the executives where they feel most and least comfortable with deploying technology. They were most willing to automate decisions in areas such as advertising vacancies, screening applicants, onboarding, salary decisions and skills development. Areas where they foresaw being less willing to rely on technology include hiring, evaluation and promotion. The importance of human interaction in such areas also underpins our second lesson.

2. The importance of employees’ emotions is widely recognised, but not yet acted on

For decades, it was commonly considered that emotions were best left out of business. This is changing, as researchers find a gap between how employees say they would like to feel about their work (e.g. excited, appreciated, satisfied, proud) and how they actually feel (e.g. bored, stressed, frustrated, tired). CPOs are increasingly held responsible for employees’ mental health and emotional well-being.

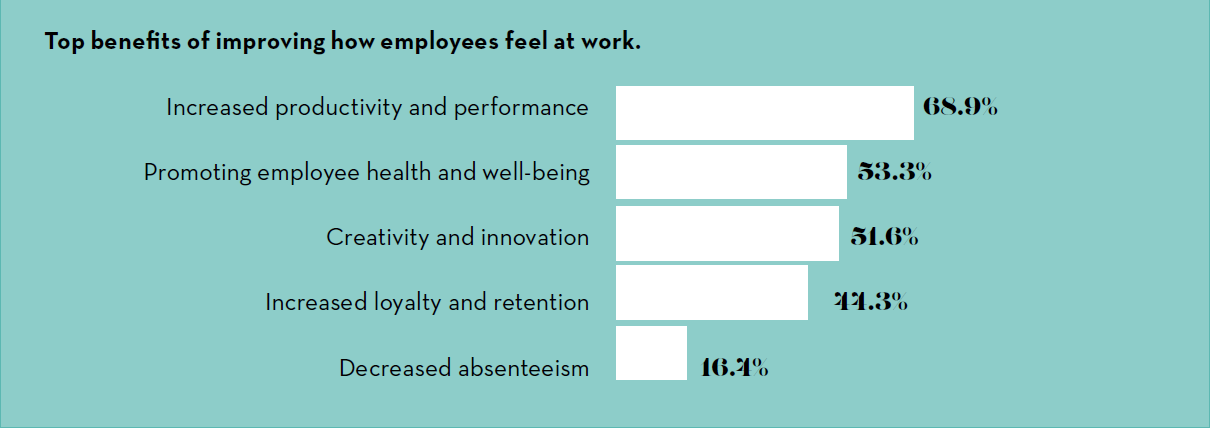

Our survey found that CPOs recognise the value of addressing employee emotions. They see the most important benefits as being in productivity and performance, followed by creativity and innovation – while other recent research points also to benefits from reducing absenteeism to enhancing loyalty and retention.

Yet how leaders should address emotions at work largely remains a black box. We asked the CPOs what they do to improve employees’ feelings. “Regularly measuring and providing feedback on how employees feel” was the most common answer – still, this was done in only just over half of the companies. Only 30% said their companies track how employee feelings affect results.

The next most common answers were holding managers accountable for how employees feel; shaping office spaces with emotions in mind; and running programs focused on well-being. Less common but interesting examples included “mental health champions” trained to foster well-being. Nobody said their company trains employees on emotional skills, despite many studies attesting to the benefits.

These findings show how much room there is to improve employees’ emotional well-being. How employees feel at work needs first to be measured, to enable emotions to be embedded in organisational processes – from how people are hired and trained, to what kinds of jobs they are asked to do. This notion of “organisational emotional intelligence” can guide companies to become more human-centered – and more welcoming for employees who have experienced career breaks, the subject of our third lesson.

3. Returnships can be a way to improve diversity, though their benefits are under-appreciated

CPOs are increasingly concerned about ways to recruit talented workers, especially from diverse groups. We asked about one concrete solution: returnships that integrate different social groups who have taken career breaks back into the workforce. This is especially relevant after the pandemic disproportionately pushed women out of the workforce to care for family members and children during school closures.

Returnships offer professionals a path back into the workplace after a career break, through a mix of paid placements, skills refreshment, networking, coaching and mentorship. While so far typically focused on highly qualified women in finance and professional services who have taken a break to start a family, they also have potential to benefit other groups of professionals.

We asked CPOs about what kinds of worker, if any, they address through returnship programs: 69% have programs to help integrate mothers returning after childcare; 57% for fathers returning after childcare; and 40% for employees returning after time off to care for adult dependents. Only 13% mentioned any other group, such as those returning from extended sick leave, military duty or sabbatical.

Executives were more likely to agree that returnship programs benefit wider society than their own organization or the returner themselves. However, women executives – who are more likely to have had personal experience of such programs – are more likely to offer them. This suggests there may be a need to shift mindsets more widely about the potential for returnships to benefit core company objectives.

A powerful opportunity to reshape the world of work

The pandemic has created both the opportunity and the urgent need to reshape the world of work in a more human- way. Every organisation needs to think about how the role of the Chief People Officer is shifting, what concrete actions they can take to better support employee well-being, and how they can create a company culture that fosters greater diversity and inclusion. Leaders in people management can pave the way to a future of work that is empathetic, caring, inclusive, diverse, flexible, adaptable, evidence-based, and – above all – people-centric.